Lawrence University is mourning the loss of Congressman John Lewis, an iconic figure who tirelessly fought for civil rights and racial justice. He taught us, the nation and the world about leadership and vision and showed us what it means to be a courageous champion of human and civil rights.

Lewis passed away late Friday following a battle with pancreatic cancer. He was 80.

Lawrence had a long relationship with the civil rights pioneer and longtime congressman. In June 2015, the school awarded Lewis an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters degree, and Lewis delivered the spring Commencement address, his third visit to the campus.

“We try to prepare each of our students for a life full of meaning, success, and consequence; Congressman Lewis provided a beautiful model of such a life each time he joined us on campus,” Lawrence President Mark Burstein said. “We will miss his voice, spirit, and enduring pursuit of equity.”

Lewis first visited Lawrence in April 1964 as head field secretary of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. He spoke at a campus-sponsored Civil Rights Week event.

He would return in February 2005 to deliver a convocation address in Memorial Chapel.

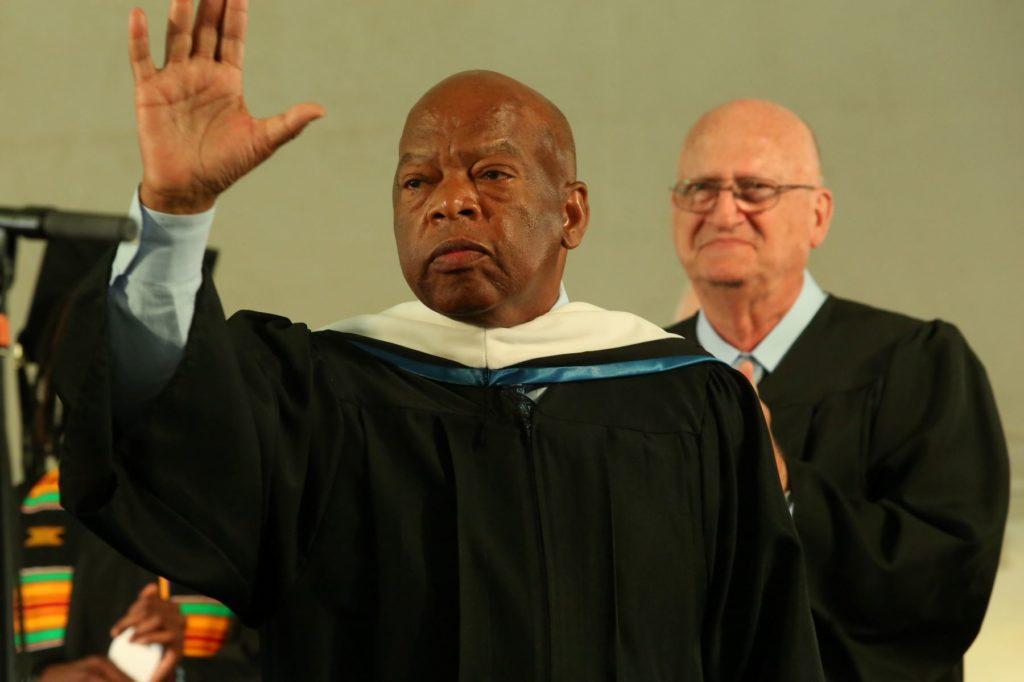

Rep. John Lewis talks with graduates and visitors to the spring Commencement in 2015.

When he returned in 2015, his story had been well chronicled, from the injuries he sustained in the historic 1965 march for voting rights from Selma to Montgomery to his leadership in the civil rights movement to his rise as an influential member of Congress, serving the state of Georgia for 34 years.

He was joined in the 2015 visit to Lawrence by Appleton native and fellow Freedom Rider James Zwerg.

In his Commencement address, Lewis told the graduates and others who had gathered on the Main Hall Green that we need to embrace unity, no matter our ethnic background, religious affiliation, or sexual orientation.

Commencement 2015: Congressman John Lewis

Congressman John Lewis delivers the principal address at Lawrence's 166th Commencement ceremony.

“We are one people, we are one family, we are one house,” he said. “We are brothers and sisters.”

He told the graduates they have a moral obligation to speak up against discrimination, encouraging them to “get in good trouble” in making the United States — and the communities in which they live — more compassionate and more inclusive.

“You can do it,” he said. “You must do it. Not just for yourselves but for generations yet unborn.”