The weather didn’t cooperate, but the work got done. And the results are beautiful.

A large mural featuring the faces of three generations of Native Americans was unveiled on the Lawrence University campus Thursday following a convocation address by Matika Wilbur, the creator and director of Project 562.

“I would never have dreamed this as I was daring to dream as a young girl,” Wilbur told a nearly full Memorial Chapel during the spring convocation.

“I’m so proud of you,” Wilbur said, addressing the more than a dozen Native American students from Lawrence and the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay who helped create the mural over the past five days. “And I’m proud of Lawrence for taking this huge step. This is a huge step to have indigenous representation on a college campus.”

The timeline for finishing the mural on the north-facing exterior wall of the Buchanan Kiewit Wellness Center was accelerated early in Wilbur’s week-long artist-in-residency because of the snow and rain that had been expected Wednesday night into Thursday morning. She worked long days with the Native students to finish the mural before the snow arrived.

The non-permanent mural, made with wheat paste, is expected to last two to five years before it begins to fade. How long an outdoor wheat paste installation lasts depends on weather conditions.

Following her convocation address, Wilbur led a walk from Memorial Chapel to the Wellness Center for a showing of the mural. A reception was held in the Steitz Hall atrium, where some of the participating students thanked Wilbur and her team for dedicating themselves to a project that reassures Native communities, especially young people, that they matter, that their faces should be seen and their voices should be heard.

Wilbur, a visual storyteller from the Swinomish and Tulalip tribes of coastal Washington, has been traveling the country as part of Project 562, using photography and art installations to connect with tribal communities and help redirect the narrative on indigenous people. The 562 is a reference to the number of federally recognized tribes in the United States at the time the project launched in 2012.

Wilbur sold most of her belongings, loaded her cameras into an RV and set out to document lives in tribal communities across all 50 states. It’s gone even beyond that, she said.

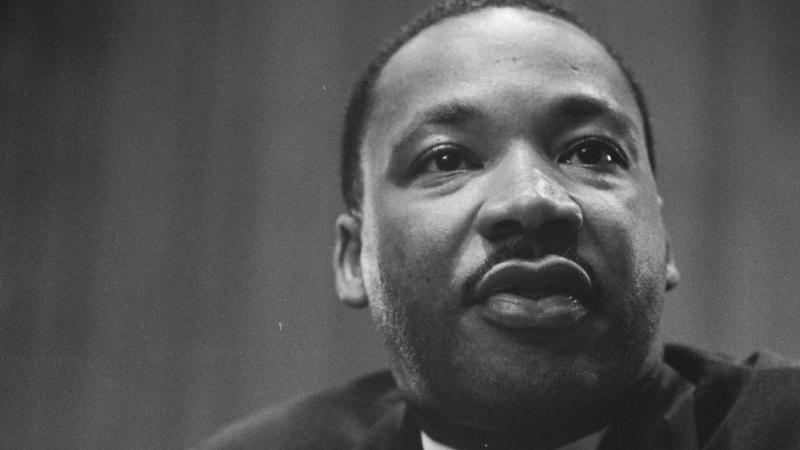

Matika Wilbur delivers her Convocation address, “Changing the Way We See Native America,” in Lawrence Memorial Chapel.

“I’ve also gone into urban Indian communities, also to Arctic communities, north of the border and south of the border and into the Caribbean islands,” she said. “So when, or if, this project is ever complete, I will have been to something like 900 tribal communities.”

Wilbur, a celebrated photographer, is expecting the travel to wrap up in about six months. After that, Project 562 will play out in books, exhibitions, lecture series, web sites, new curriculum and podcasts.

She talked about her long and winding journey during Thursday’s convocation, which included a performance by traditional Menominee flutist Wade Fernandez, an Oneida drum/dance group and an opening invocation spoken in the Menominee language by Dennis Kenote, chairman of the Menominee Nation Language and Culture Commission.

Brigetta Miller, an associate professor of music in the Lawrence Conservatory of Music and a member of the Stockbridge-Munsee (Mohican) Nation, introduced Wilbur. Miller is a 1989 Lawrence graduate who teaches ethnic studies courses in Native identity, history, and culture and works with Native American students on campus as a faculty advisor to the LUNA (Lawrence University Native Americans) student organization. She hailed Wilbur’s convocation and mural project as a historic moment for Lawrence, the Native students who are here and area tribes.

“Matika has a magical way of giving our Native students and their allies permission to acknowledge and be proud of their own cultural traditions, families and indigenous ways, even in spaces that may have not been historically designed for us,” she said.

During the week of activities, students could be heard speaking to one another in their Native languages, Miller said, calling that a reflection of the pride that emanates from this project.

“This work is more than making art for the sake of social justice,” Miller said. “It’s a way to truthfully show who we are. It’s a way for us to tell our own story.”

Telling that story, and giving young people an opportunity to embrace their own story, is what first ignited Project 562, Wilbur said. She had been asked to teach at a tribal school in the northwest, and at first hestitated.

“It turns out I loved working with kids,” she said. “It did something special for me. It recentered me in my community and helped me to realize my purpose and realign me with what I am meant to do. It taught me that I have this role where I’m supposed to feed the people, I’m supposed to participate in making my community a healthier, happier place.”

That experience teaching led her to her next revelation, one that would put her on the road to Project 562. She said she finally fully realized that the true Native American story wasn’t being told or taught.

“It was while I was teaching, I saw over and over and over again that the American dream did not include us,” Wilbur said. “I realized that when Lincoln said, ‘For the people,’ he did not mean Native American people. I came to understand that the core of our curriculum is not based in truth. It does not cultivate our indigenous intelligence.”

So she set out to change that, one photograph and one art installation at a time.

The large mural now visible at the center of the Lawrence campus speaks to that — a new mindset, a new message about respect and truth and inclusion that needs to reverberate long after the Project 562 team has left Appleton.

“As a Native professor here on this campus, this project gives me hope for the future generations,” Miller said. “It’s history unfolding before our eyes.”