For all the Lawrentians out there who are working from home, communicating with the office from afar for reasons of choice or pandemic-related necessity, take heart in this fun connection. The scientist who was perhaps the earliest champion of working remotely, who has been called the father of telecommuting, who was publishing books on the subject nearly 50 years ago, well before personal computers were even a thing, is an alumnus of Lawrence University.

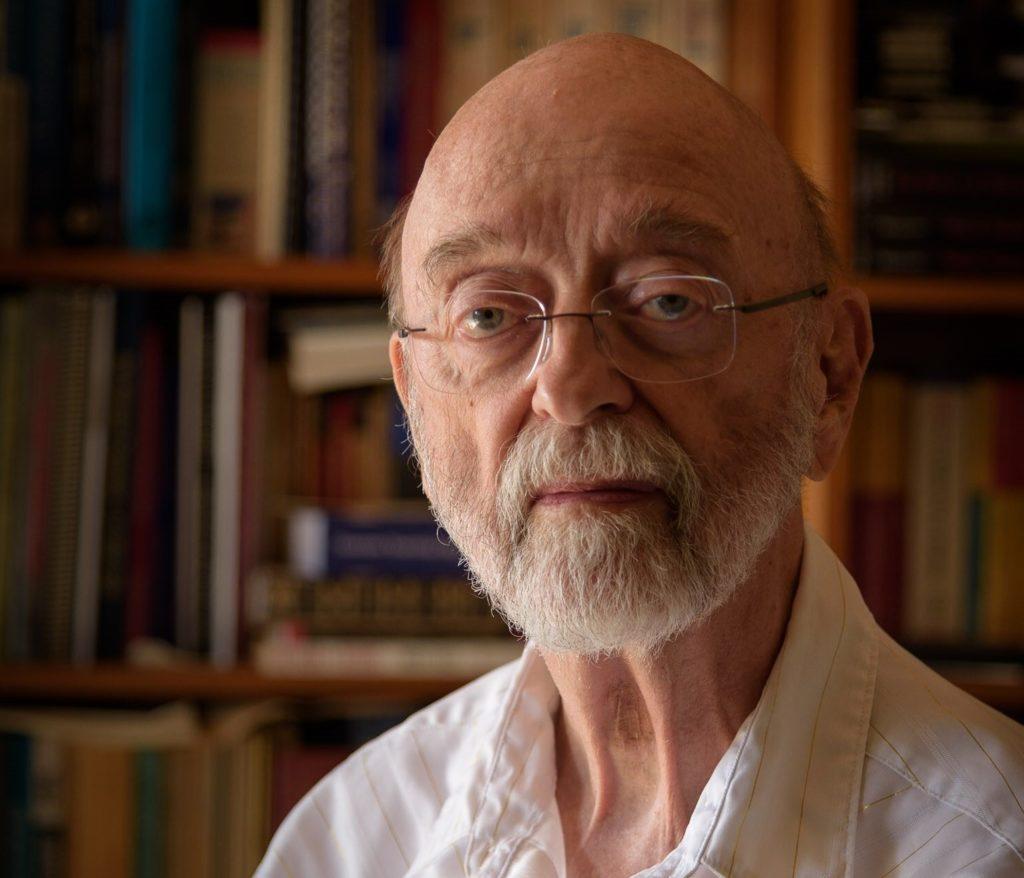

Meet Jack Nilles ’54, Lawrentian and visionary.

He studied physics at Lawrence. He would go on to become an accomplished physicist, working for a decade and a half at the U.S. Air Force’s Aerial Reconnaissance Laboratory in Dayton, Ohio, and The Aerospace Corporation and serving as a consultant with NASA, President Kennedy’s and President Johnson’s Science Advisory Council (PSAC), and the National Science Foundation (NSF).

“In the late ’50s and ’60s, I was basically a rocket scientist, devising reconnaissance satellites, for the most part,” Nilles said from his home in Los Angeles. “Most of it is highly classified stuff.”

Then came a career switch in the early 1970s, when Nilles shifted from rocket scientist to the director of interdisciplinary research at the University of Southern California, a position created for him so he could follow his theory that remote working, then unheard of, would be good for business and even better for the environment.

Living amidst Los Angeles’ notorious traffic congestion and seeing the increasing volatility around air pollution and other emerging oil and gas issues, Nilles floated the idea that office workers need not go into the company’s corporate offices to be effective. He envisioned satellite offices located closer to where employees lived, the payoff being employees who are less stressed and more productive, employers saving money by forgoing expensive downtown real estate, and an ecosystem that would benefit from a reduction in commuter traffic.

“Most of the traffic was people going from home to work and back,” Nilles said. “And much of that was people going to their offices, not to factories or other workplaces where they had to be there. When they get to the office, they get on the phone and talk to somebody somewhere else. I said, ‘Why don’t they just do that from home in the first place?’ This was around 1970.”

He delivered the idea to business leaders, including his own employer.

The response? Eh.

They were intrigued, but not quite ready to let employees out of sight.

“The experiment was a success”

Once at USC, beginning in 1972, Nilles put his idea to the test with a team of scholars across numerous disciplines and in partnership with a national insurance company that would serve as the study’s subject. Per the nine-month study, worker productivity went up, health care costs went down, and infrastructure costs dropped. If implemented nationwide, the insurance company could save upwards of $5 million a year, the study suggested.

“So, the experiment was a success,” Nilles said. “But the company said, no, we’re not going to do that. From every direction, we got resistance. That was my early lesson that this was going to be hard to sell. They’re used to business as usual. I’ve been fighting that ever since.”

Even now, 48 years later, only about 3 percent of employees in the United States work from home more than half the time, according to a report in The New Yorker. But the COVID-19 pandemic has, at least for now, made it more the norm than the exception. Technology allowed for a rapid transition when the pandemic hit in March, introducing people en masse to the joys and frustrations of Skype and Zoom – find the mute button, please — and turning attention-seeking dogs, cats, and home-bound children into office cohorts.

Now we’re five months into the global pandemic and this work-from-home thing has gotten less awkward. Nilles, 87 and still working 40 hours a week, said he’s hearing from people who say it’s already feeling, well, normal.

A scientist with a deep liberal arts mindset that was nurtured during his four years at Lawrence, Nilles saw those possibilities back in the early ’70s, even if others could not, when personal computers, laptops, smart phones, and teleconferencing were still fantasy. In 1976, he published the book, The Telecommunications-Transportation Tradeoff, posing the question: “Can telecommunications and computer technologies be substituted for some portion of urban commuter traffic?”

It turns out, yes.

The book, updated and reprinted in 2007, detailed the 1973-74 study and posed questions that remain relevant today. (Yes, the book is available in Lawrence’s Mudd Library.)

While Nilles’ early work focused more on satellite offices than home offices, the message has held up through a bevy of technology advancements: Instead of viewing traffic congestion, and related urban sprawl, as a transportation issue, look at it as a communication issue. He coined the terms “telecommuting” and “telework.” He would write five books in all, and in 1980 co-founded with his wife, Laila, the management consulting firm JALA International. The company became heavily invested in developing good remote work practices, and in 1989 Nilles left USC to run the company full-time.

“It has clearly altered things”

Fast forward to 2020, with the pandemic steamrolling the economy and altering work and school processes, and you find Nilles suddenly getting new attention. The New Yorker and the New York Times, among other media outlets, have shined a fresh light on his pioneering work. “Jack Nilles envisioned a complete transformation of work, in which the central office might disappear – a steam engine giving way to a network of motors,” Georgetown University’s Cal Newport wrote in a May feature in The New Yorker. In July, the Harvard Business Review and Vox highlighted Nilles’ early efforts and the difficult road that remote work has traveled since.

“I keep saying lately, ‘after 48 years, I’m an overnight success,’” Nilles joked.

Work from home isn’t for everybody. Many, maybe most, want to be in the office, at least part of the time. Some companies that had plowed ahead with going remote have pulled back in recent years, tech giants Yahoo and IBM among them. But the pandemic has forced employees and employers to explore again what the possibilities might be, and some are now finding it to their liking, Nilles said.

“I think the pandemic clearly is the force that I did not have available to me at the time,” he said. “Now that it’s here, it has clearly altered things, and I think permanently.

“Now I see headlines in the New York Times and the Washington Post every couple of days where companies are saying, ‘Well, gee, now we look at the costs, particularly in big cities, and we’re spending all this money on office space that we really may not need.’ As it turns out, surprise, surprise, people are more productive when they’re working remote than when they’re working in the office. That’s what we’ve been trying to tell you for 48 years.”

A rush to stay remote would, of course, create other issues, from financial implications in the commercial real estate market to sociological and psychological impacts within the work force. Watching how people respond and adjust as the pandemic rewires what we consider normal will be fascinating, Nilles said.

“We’re still in the middle of a giant experiment. … My original objective in 1973 was to see if this is feasible in a contemporary American business environment. Now, it’s clearly feasible. Now we have to go in and figure out what else does all this mean.”

Who better than the father of telecommuting to be part of that conversation? A Lawrentian, at that.

While Nilles’ company is mostly dormant, he still posts to his JALA Thoughts blog regularly, gets tapped as a consultant on creating remote work environments, and speaks on issues of climate change. He calls his time at Lawrence key to being able to nimbly navigate in the worlds of aerospace science, business productivity, and environmental sustainability over five decades, his liberal arts roots in play every step of the way.

“At Lawrence, I learned a little bit about everything,” he said. “How to deal with people who were experts in all these different disciplines. That was absolutely key to my being able to function in these different worlds.”

If you need to know more, you can find Nilles at home, where his office has been located for the past 31 years.