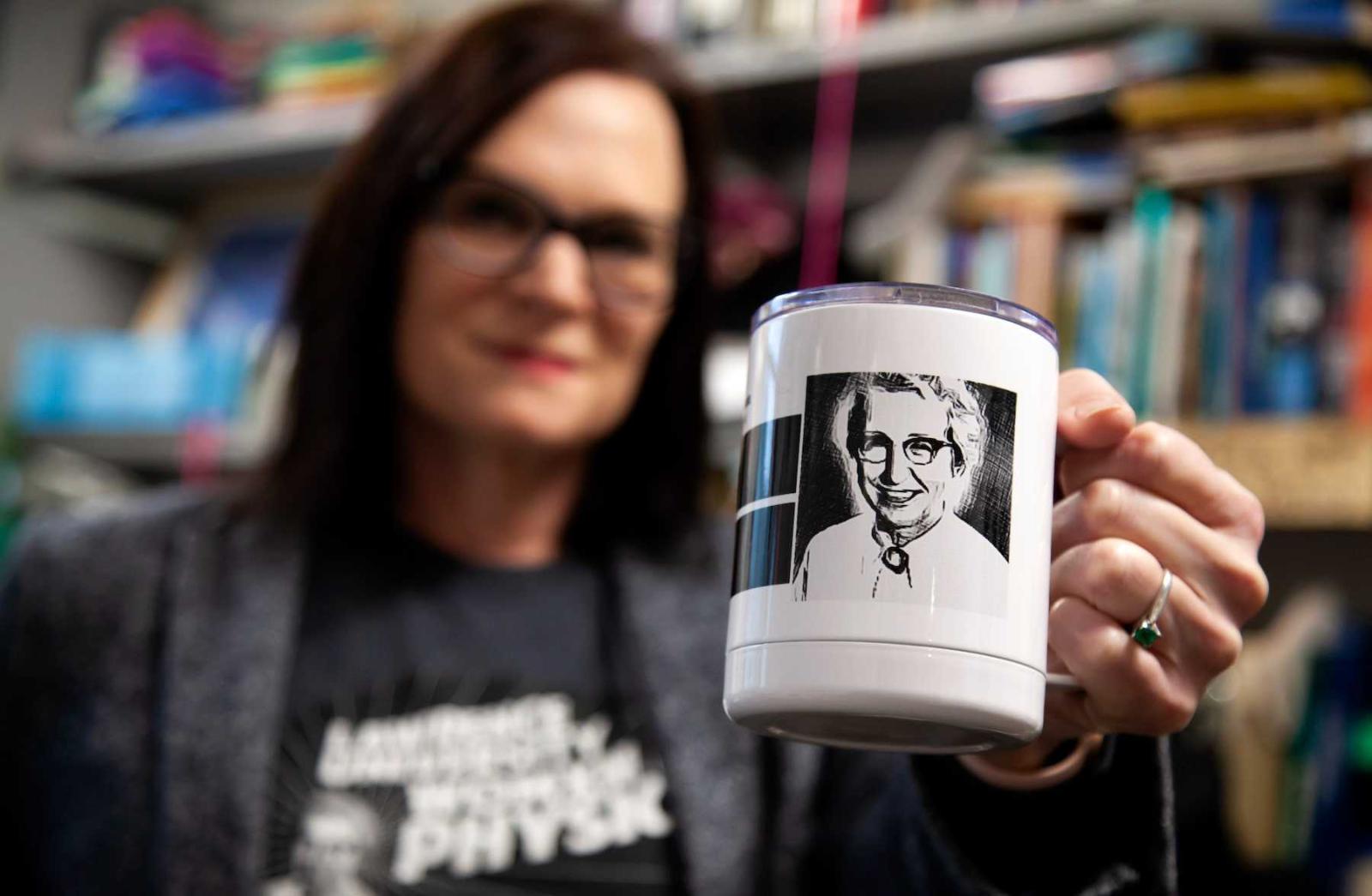

A painting of Elda Anderson, created by a former Lawrence University physics student, hangs on the wall in Megan Pickett’s cramped office in Youngchild Hall. On her desk is a coffee mug baring the image of Anderson; it’s among the physics professor’s most prized possessions.

And circled on her calendar is Oct. 5, when Lawrence’s Society of Physics Students and Women in Physics will honor the birthday of Anderson in what they hope will become an annual tribute.

Elda Anderson, after all, is well known in and around the first floor of Youngchild Hall—revered as a pioneering scientist and educator who taught at Milwaukee-Downer College and was recruited in the early 1940s to work on the Manhattan Project, the code name for the secret development of the atomic weapon that would be used to end World War II. She is credited with the creation of the first pure sample of uranium-235, key to the development of the bomb. And, spurred by what she saw and experienced in her three and a half years in Princeton, New Jersey, and then Los Alamos, New Mexico, she would spend the latter part of her career warning of the dangers of the atomic age and pioneering new research in the protection of people from radiation.

Yet, save for members of the Health Physics Society, a professional organization she co-founded, and historians who have studied the Manhattan Project, Anderson remains mostly out of public view once you leave Youngchild Hall.

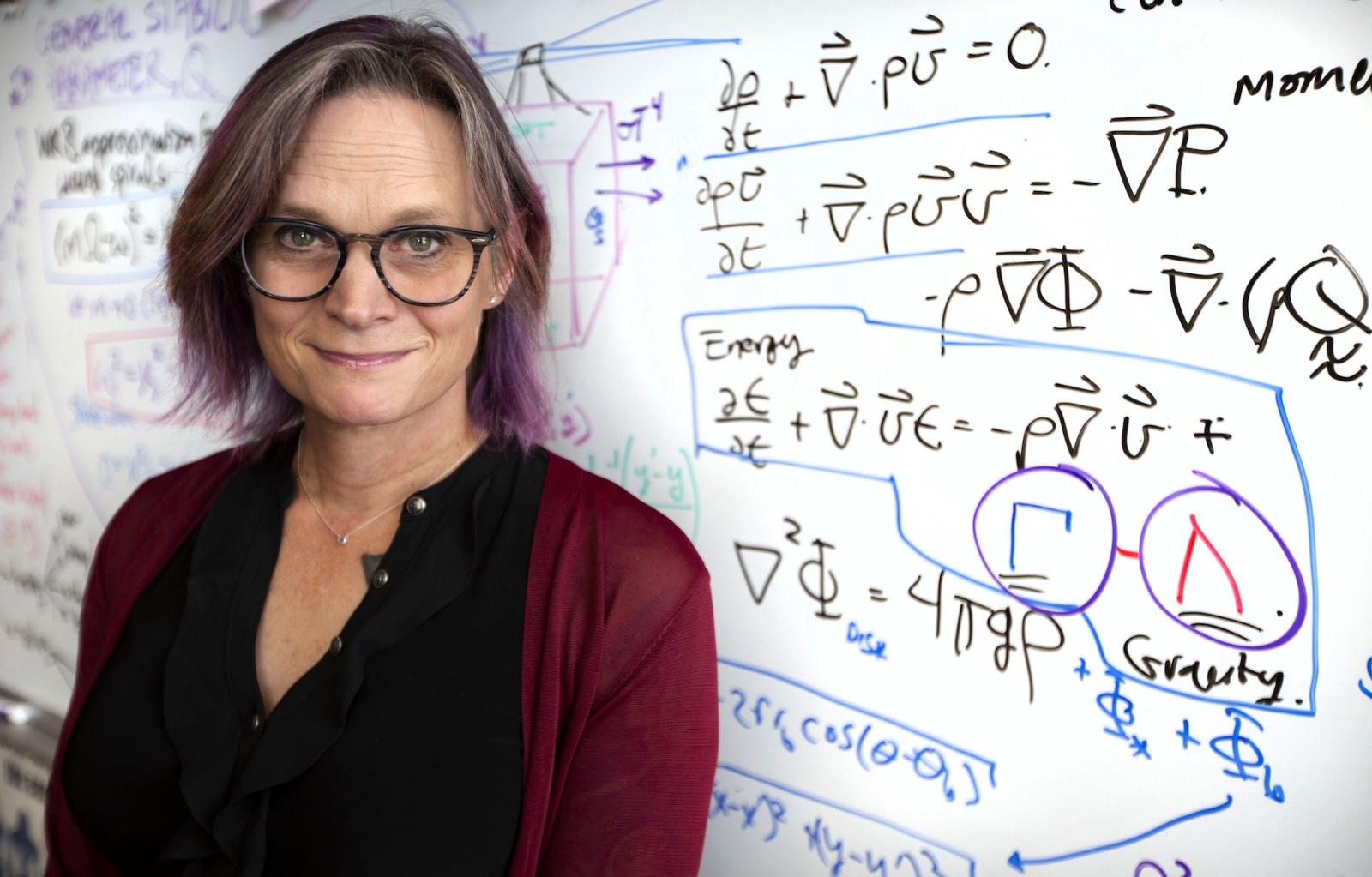

With Green Lake High School yearbook information on the screen behind her, Megan Pickett delivers a Winter Term talk about the remarkable life of Elda Anderson. (Photo by Danny Damiani)

Pickett, an associate professor of physics, is on a mission to change that—at the very least at Lawrence, which merged with Milwaukee-Downer in 1964, three years after Anderson’s death. She is working on a biography of Anderson, one that details Anderson’s deep contributions to science, her critical role in the Manhattan Project, her dedication to teaching, her place in Milwaukee-Downer and Lawrence history—she was the first woman to earn tenure in physics and the first woman to serve as chair of the Physics Department—and her deep roots in Wisconsin. She grew up in Green Lake, earned a bachelor’s degree from Ripon College and a master’s and Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and served as principal of Menasha High School before joining the Milwaukee-Downer faculty.

As Lawrence celebrates the 175th anniversary of its founding in 1847, it also celebrates the shared history of Milwaukee-Downer. Anderson is infused in that history, a brilliant scientist and educator who taught at the Milwaukee women’s college from 1929 to 1941 and again from 1945 to 1949.

It is there that Pickett feels a strong connection. In 2010, Pickett became the first woman at Lawrence to earn tenure in physics, and she would later become the first woman to chair the Physics Department—second only to Anderson when the Lawrence and Milwaukee-Downer histories are taken together.

Learn more about Milwaukee-Downer history

It was a note in 2010 from Lawrence’s archivist, Julia Stringfellow, shortly after Pickett’s tenure appointment was announced, that first alerted her to Anderson. The connection immediately resonated.

“I’ve always been interested in elevating women’s voices in the sciences,” Pickett said.

But what she found when she went looking for more was disappointing. The information on Anderson available online is limited. There is no biography. There is no detailed reporting of her contributions to science, only general references to the Manhattan Project and her teaching career. She is part of a generation of women scientists whose histories are mostly hidden.

So, after a number of starts and stops over the past dozen years, Pickett made a commitment in the fall to tackle the biography project. She wants to raise Anderson’s profile—and that of Milwaukee-Downer—during Lawrence’s 175th anniversary year and she wants to begin laying the foundation for a significant celebration in 2024 that will mark Anderson’s 125th birthday.

Megan Pickett: “I’ve always been interested in elevating women’s voices in the sciences."

Pickett began by making Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests to learn more about Anderson’s work on the Manhattan Project at both Princeton and Los Alamos—some of it remains classified—and she is seeking printed materials from the Milwaukee-Downer archives, from Anderson’s other academic and professional stops, and from various historical societies. She located a great nephew, hoping to learn more about the family’s history.

“After finding there is really nothing substantial written about her, I got upset and decided I’ll write it myself,” Pickett said.

Much of Pickett’s writing will zero in on how Anderson, then in her 12th year teaching at Milwaukee-Downer, caught the attention of U.S. government officials who were launching the secretive Manhattan Project. She had been doing exacting research in spectroscopy, the study of the absorption and emission of light and other radiation by matter.

“She had earned her Ph.D. at Madison in looking at very fine detail of two metals, cobalt and nickel,” Pickett said. “You vaporize the metal and then you shine that light across essentially a prism, and that would make a rainbow pattern on a distant screen. You can then count the different colors, and it’s from that pattern of colors that you could determine the atomic structure of these elements. She was looking at very specific kinds of elements, and she was looking at such fine detail that the light was spread over 21 feet. She was looking at lines of light that had hundreds of thousands of peaks per centimeter.”

As Anderson finished her Ph.D. in 1941—while still teaching at Milwaukee-Downer—World War II was raging. With fears growing that Germany was closing in on the development of a weapon using nuclear technology, the U.S. government launched the Manhattan Project in 1942, bringing together select scientists and the U.S. military in what became a frantic race to develop an atomic bomb.

“So, Elda is doing all this work and she’s finding atomic structure at such an incredible level by hand that she catches the attention of the war office,” Pickett said.

Anderson initially joined the war effort at Princeton University, a lead player in nuclear physics research. But in early 1943, Project Y was formally launched, amid much secrecy, as the next step in the Manhattan Project. Theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, who had been working on the concept of nuclear fission, was named director of the Los Alamos Laboratory in northern New Mexico. Anderson would be transferred to Los Alamos shortly thereafter, with the study of fission as her focus.

“She was one of the first 100 to arrive in Los Alamos,” Pickett said.

Thousands more would follow as the research project became a city unto itself.

“She was hired because she was a great spectroscopist and experimentalist,” Pickett said.

It didn’t take long for Anderson’s work to draw notice, according to a 2018 report from the American Nuclear Society: “Working in a cyclotron group, Dr. Anderson focused mainly on spectroscopy and neutron cross section measurements. Her work led her to produce the lab’s first sample of uranium-235.”

That was a big deal, Pickett said. Unlike uranium-238, U235 is fissile, meaning it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It marked a significant turning point in the research.

The Atomic Heritage Foundation said of Anderson: “Her diligence and intellect would make her a key figure in the atomic bomb’s creation.”

On July 16, 1945, in a remote desert location in New Mexico—two and a half years after Project Y had launched—the Trinity Test would become the first successful detonation of an atomic bomb. Anderson was on hand to witness the test.

“We knew that the bomb was perfected, that it would work,” Anderson told the Milwaukee Journal in January 1946. “We were only waiting for news of the time and place of its use.”

The hope was that the successful Trinity Test would lead to an immediate surrender by Japan. That did not happen, and on Aug. 6, 1945, the “Little Boy” bomb was dropped over Hiroshima; three days later, the “Fat Man” bomb was dropped over Nagasaki, leading to Japan’s surrender and the war’s end.

“Without Elda, we don’t have a pure sample of U235 on time, the bomb doesn’t work, and the war doesn’t end, arguably,” Pickett said. “She played a critical role in the Manhattan Project.”

Following the war’s end, Anderson would return to Milwaukee-Downer and teach for four more years. She was celebrated upon her return, but she came back to campus with a stark message: The nuclear age that has dawned puts the world in peril.

“Without Elda, we don’t have a pure sample of U235 on time, the bomb doesn’t work, and the war doesn’t end, arguably."

Megan Pickett on Elda Anderson's contributions to the Manhattan Project during World War II

Pickett found a May 1946 story in Milwaukee-Downer’s Hawthorn Leaves, written shortly after Anderson returned to campus, that describes her as a “remarkable person” beloved by her students.

And Pickett found a letter written by Anderson to alumni in 1947—part of Milwaukee-Downer Day—that implores them to be vigilant about the dangers that have come with the development of the atomic bomb and the race of nations to develop and grow their nuclear powers.

“The second year of this Atomic Age has begun, and we cannot close our eyes to the fact that an atomic armament race has begun,” Anderson wrote. “Be assured that if another war comes, atomic armaments will be used. Thus, the real task before the world is to end war, and one has only to recall Hiroshima and Nagasaki to know that we must succeed.”

By 1949, Anderson had turned her focus to the dangers of radiation. She left Milwaukee-Downer to become the first chief of education and training for the Health Physics Division at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. She went on to co-found the Health Physics Society, and she led U.S. radiation protection training programs, training the first specialists in the field of health physics.

“She helped Vanderbilt University create a master’s degree program in health physics,” Pickett said. “She became president of the Health Physics Society, creating these special classes. She’d travel internationally, to Sweden, Belgium, India, elsewhere, teaching radiation safety protocols, some of which we still use today.”

In 1956, Anderson was diagnosed with cancer—first leukemia, then breast cancer.

“It’s not clear whether it was due to her war research, but a lot of people believed it was,” Pickett said.

She died in 1961, just shy of her 61st birthday. Her body was returned to Wisconsin for burial in Green Lake.

A year later, the Health Physics Society launched the Elda Anderson Award, given to a scientist under the age of 40 who makes significant contributions to the profession of health physics. It has now been awarded annually for six decades.

For Pickett, the search for more information on Anderson is ongoing. She was anticipating the arrival of 10 boxes of materials from the Milwaukee-Downer Archives, housed at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. And she awaits responses to her FOIA requests from various departments and agencies in the federal government.

Her commitment to the project, to raising Anderson’s profile, grows by the day.

“I like to refer to her as the Milwaukee Marie Curie,” Pickett said, referencing the Polish and naturalized-French physicist and chemist who pioneered research on radioactivity. “She really has a lot of similar aspects to her story.”

She wants to share Anderson’s journey to Milwaukee-Downer, which included her undergraduate years at Ripon, a master’s in physics and a doctorate in atomic spectroscopy from UW, a stint teaching at Estherville Junior College (a predecessor to what is now Iowa Lakes Community College), and two years working as a science teacher and principal at Menasha High School. She wants to share how and why Anderson came to be part of the Manhattan Project, and she wants to document how those experiences led her into the burgeoning world of health physics.

“I have been living with Elda in my mind for the last 12 years or so, ever since I got that message from our archivist,” Pickett said. “I want to tell her story. And I can’t wait for people to not have to ask me who that is.”

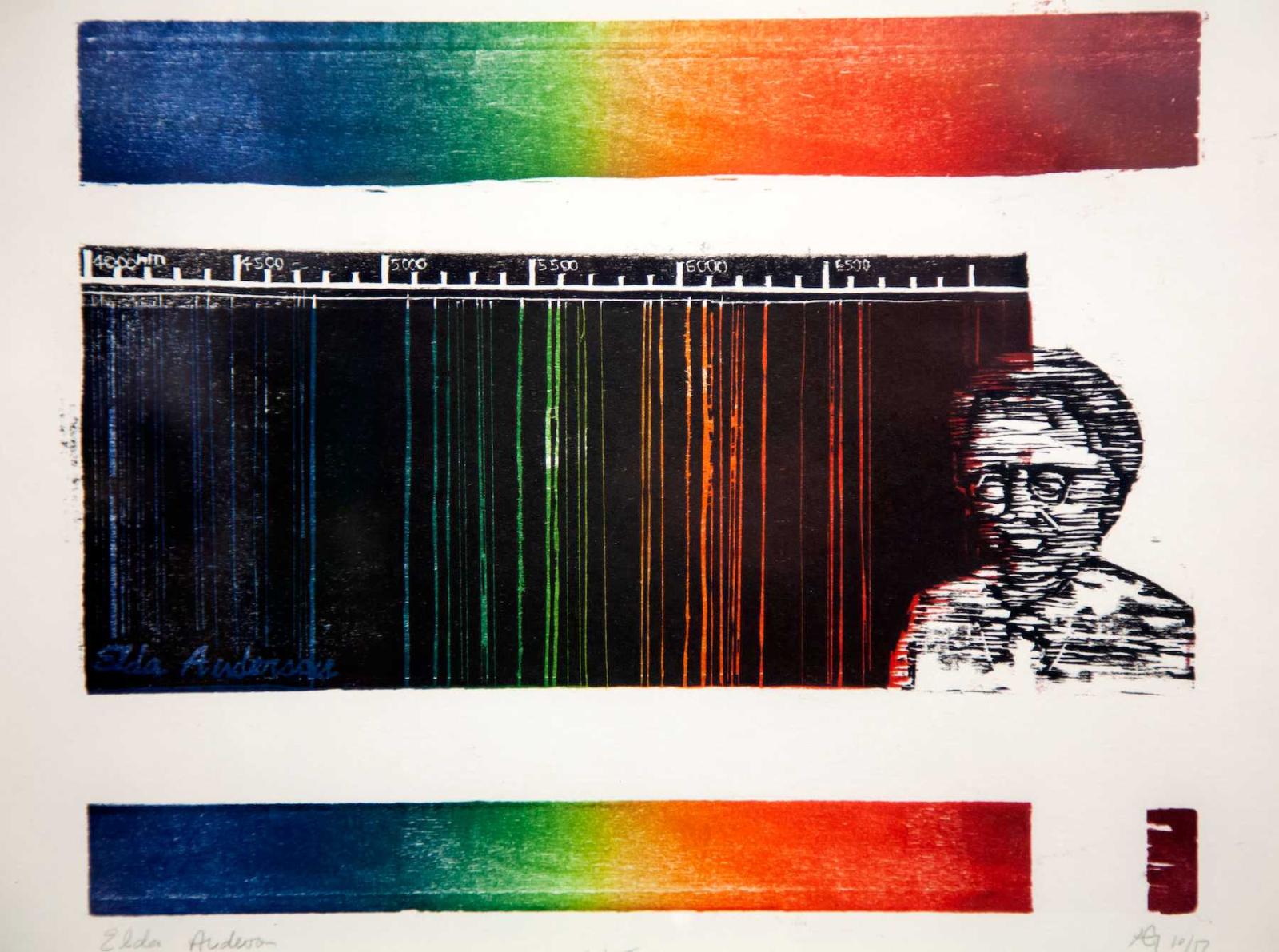

A painting featuring Elda Anderson hangs in Megan Pickett's office.

About the painting

The painting of Elda Anderson that hangs in Megan Pickett’s office was created by Aedan Gardill ’18, a physics major now doing graduate work in physics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison—just as Anderson did nearly a century ago. The painting incorporates a portrait of Anderson taken from her days at Oak Ridge National Laboratory and the Health Physics Society, about 1957. The middle strip is a representation of the light emitted by cobalt and nickel. For her dissertation, Anderson constructed a spectrometer and studied the patterns of light given by highly ionized nickel and cobalt—samples that were super-heated. Each strip of color is due to the tiniest spacing between electron orbits in the elements. To accomplish her work, the Ni and Co sources needed to glow across 21 feet to a 5-foot plane of glass coated in photographic emulsion. She then measured the hundreds of fine lines by hand, and from that was able to piece together the detailed atomic structure of both elements. It was this dedication and precision that attracted the attention of the Office of Scientific Research and Development at Princeton in 1942, which would lead to her recruitment in 1943 to Project Y, the Los Alamos site for the Manhattan Project.